Executive Summary

The United States has entered a decisive phase in which rising sovereign debt, structurally higher fiscal deficits, and a diminishing global appetite for U.S. Treasuries are reshaping the macro-financial architecture that has underpinned the global economy for decades. While the United States retains unparalleled financial depth and military power, the debt dynamics accumulated since the early 2000s — accelerated by the pandemic response — are now interacting with persistent inflationary pressures, rising interest burdens, and shifts in global reserve composition. These developments imply that the traditional framework of U.S. “Monetary Dominance,” in which the Federal Reserve freely adjusts interest rates to stabilize prices and employment, is giving way to Fiscal Dominance, where monetary policy becomes constrained by the government’s debt-servicing capacity.

This paper argues that the ultimate constraint on U.S. debt issuance is not the statutory debt ceiling, market liquidity, or default risk, but rather inflation. Inflation is the single variable capable of generating social, political, and market resistance strong enough to impose a hard boundary on debt expansion. In this context, gold becomes a strategic asset — not merely a commodity — because it is the only non-liability reserve asset that central banks can hold without counterparty risk. Historically, periods of fiscal dominance have coincided with major gold repricing episodes, including the 1933–1934 revaluation under Franklin Roosevelt and the 1971–1973 breakdown of the Bretton Woods system.

As the U.S. transitions deeper into fiscal dominance, the likelihood of gold repricing — either explicitly through policy or implicitly through market mechanisms — rises. This report examines the structural forces behind U.S. debt expansion, inflation constraints, the role of gold in global reserves, and the strategic implications for investors in sovereign bonds, foreign exchange, commodities, and alternative assets.

1. Introduction: A Global System Under Stress

The global macroeconomic regime that dominated 1980–2020 was defined by four interacting pillars:

- Low and stable inflation

- Declining interest rates

- Expansion of global trade and capital flows

- Unlimited global demand for U.S. Treasury securities

This environment allowed the United States to accumulate large fiscal deficits without visible constraints, as declining interest rates reduced the cost of servicing debt. However, by 2025 this environment has fundamentally changed.

- Globalization has plateaued.

- Geopolitical tensions have reshaped supply chains.

- Demographics in advanced economies have turned inflationary.

- The U.S. government’s debt load has exceeded $35 trillion, over 120% of GDP.

- Interest payments have surpassed $1 trillion annually, rivaling or exceeding defense spending.

- Foreign central bank demand for Treasuries has fallen from 34% of outstanding supply in 2010 to ~23% today.

The result is a structural shift in the macro regime where fiscal conditions dominate the policy environment and monetary policy becomes reactive rather than preemptive. This report explores three interconnected themes:

- The limits of U.S. sovereign debt

- The strategic role of gold and the possibility of repricing

- Inflation as the ultimate constraint on fiscal expansion

2. The Structure of U.S. Fiscal Dominance

2.1 Definition and Diagnosis

Fiscal dominance occurs when:

The primary function of monetary policy is no longer fighting inflation but ensuring the government can service its debt.

The United States is now showing the classic symptoms of fiscal dominance:

- Rising interest rates directly destabilize the fiscal balance.

- Interest payments exceed discretionary spending categories.

- The Federal Reserve cannot normalize policy without causing debt-servicing distress.

- Treasury issuance dictates monetary operations.

- Liquidity in the Treasury market becomes a national security priority.

These conditions shift the Federal Reserve from an inflation-targeting institution to a funding-stability institution.

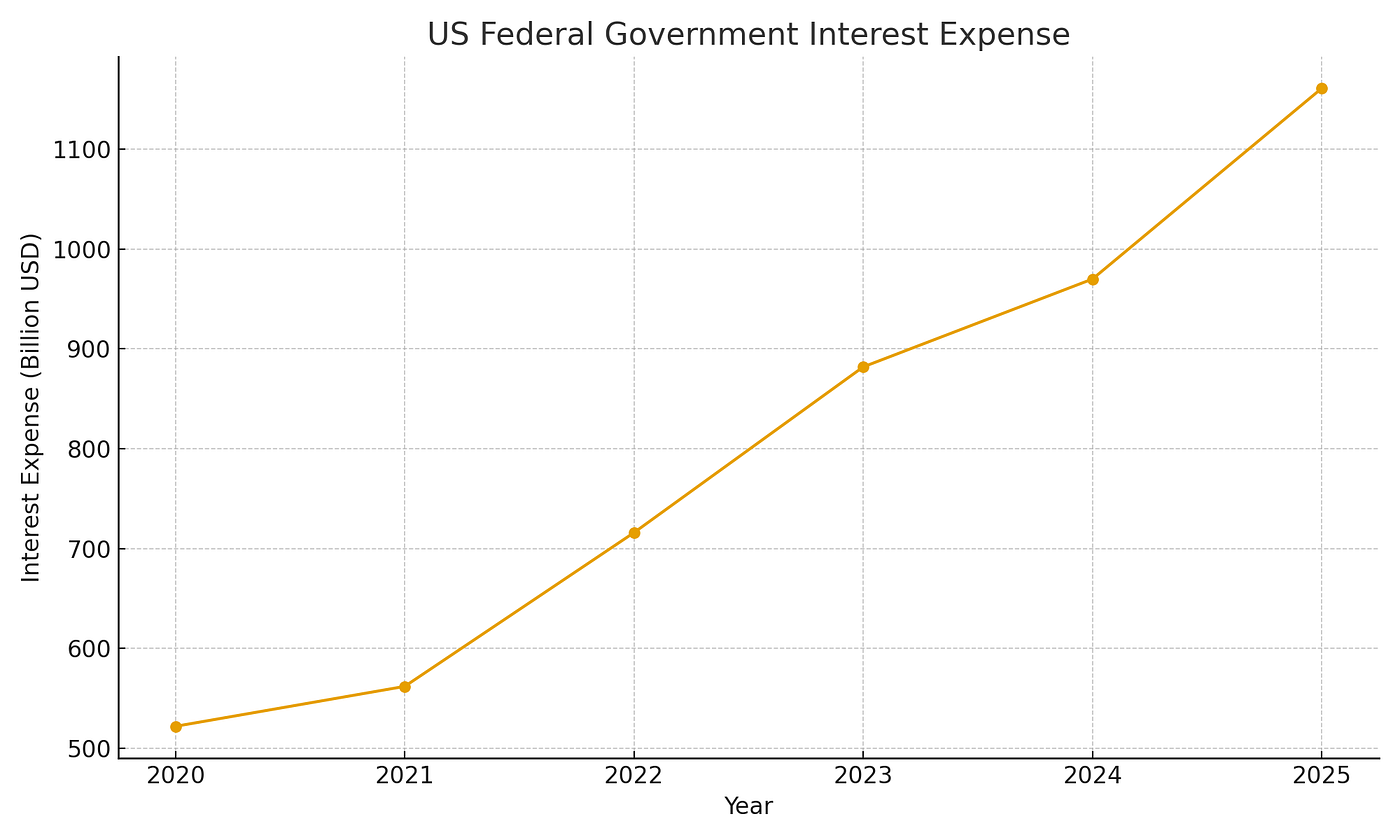

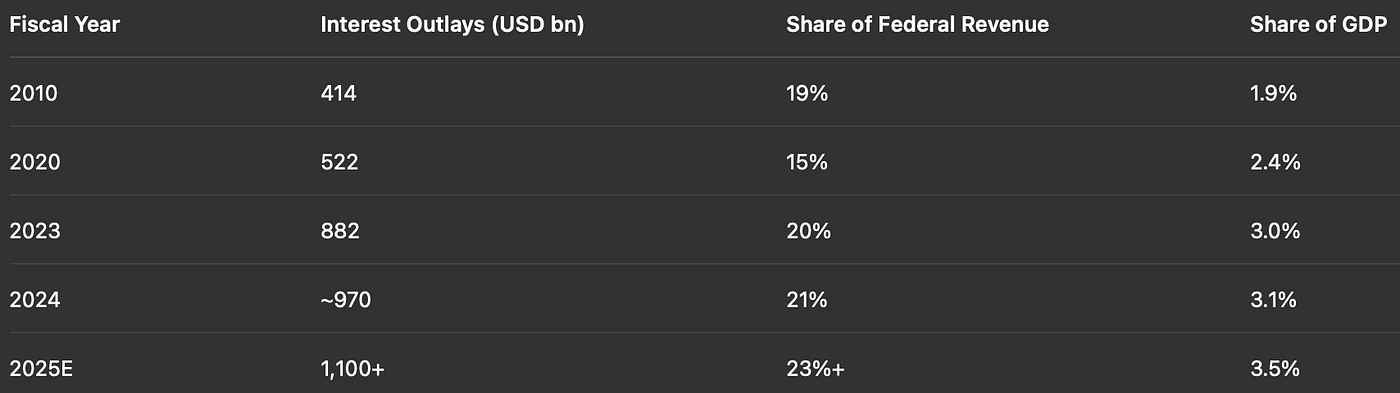

2.2 The Surging Cost of Interest Payments

Interest on federal debt is the clearest indicator of fiscal stress:

These numbers matter for a simple reason:

Every 1% increase in average interest cost adds roughly $350 billion annually to the federal deficit once rolled through the curve.

At current debt levels, sustained high interest rates are fiscally incompatible.

2.3 Treasury Issuance and the Role of Foreign Buyers

Foreign holdings of Treasuries have been declining:

- Japan: down ~$230 billion from its peak

- China: down ~$700 billion

- OPEC nations: shifting reserves toward gold

- Emerging markets: reserving less in USD and more in diversified assets

Global reserve managers are increasingly reluctant to accumulate U.S. debt at real yields that remain negative after adjusting for forward inflation uncertainty.

This forces the Federal Reserve into the position of implicit or explicit buyer of last resort, making monetary policy dependent on Treasury funding needs.

2.4 Why Fiscal Dominance Limits Monetary Policy Independence

When the central bank raises interest rates:

- The government’s debt-service cost rises

- Banks suffer mark-to-market losses on Treasury holdings

- Money-market funds drain liquidity via reverse repos

- Treasury auctions require higher yields, accelerating the debt spiral

This means the Federal Reserve cannot fight inflation with the same tools that worked historically. Any aggressive tightening risks destabilizing the largest sovereign debt market in the world.

3. Sovereign Debt Sustainability and the Inflation Constraint

3.1 The Real Limit: Not the Debt Ceiling, but Inflation

The U.S. debt ceiling is a political construct, raised more than 100 times since 1940. The real constraint on sovereign borrowing is not formal legislation but the social and economic repercussions of inflation.

Inflation acts as the true boundary because:

- It erodes real incomes

- It destabilizes political coalitions

- It shifts voter behavior

- It weakens the global credibility of the currency

- It raises long-term interest rates by increasing risk premiums

- It restricts the Federal Reserve’s ability to monetize debt

Unlike deficits, inflation cannot be hidden. It is the single fiscal variable that voters directly perceive.

3.2 The Political Economy of Inflation

The social tolerance for inflation in the United States is low:

- Above 3–4%: political pressure intensifies

- Above 5–6%: middle-class living standards deteriorate

- Above 7–9%: bipartisan backlash emerges

- Above 10%: a monetary reform cycle becomes possible

Thus, inflation is the mechanism that forces fiscal consolidation — or, alternatively, forced monetary accommodation to maintain short-term stability.

3.3 Debt Growth vs. Nominal GDP Growth: A Mathematical Dead End

For debt to be sustainable:

Nominal GDP growth must exceed the effective interest rate on government debt.

After 2021:

- Nominal GDP slowed

- The effective interest rate rose sharply

- Debt growth accelerated

This combination leads to a mechanical debt spiral unless inflation rises or interest rates are repressed. Historically, sovereigns have chosen:

- Financial repression (forced low real yields)

- Inflation above interest rates

- Asset revaluations (typically gold)

The United States has relied heavily on (1) and (2). It may increasingly require (3).

4. Gold in the Global Monetary System: From Commodity to Strategic Reserve Asset

4.1 Gold’s Unique Position

Gold is the only major asset class that:

- Is not a liability

- Does not depend on any government’s solvency

- Has no default risk

- Does not require settlement through the dollar system

- Can be accumulated without revealing real-time transactions

This makes it the ultimate hedge against fiscal dominance.

4.2 Central Bank Demand for Gold Has Surged

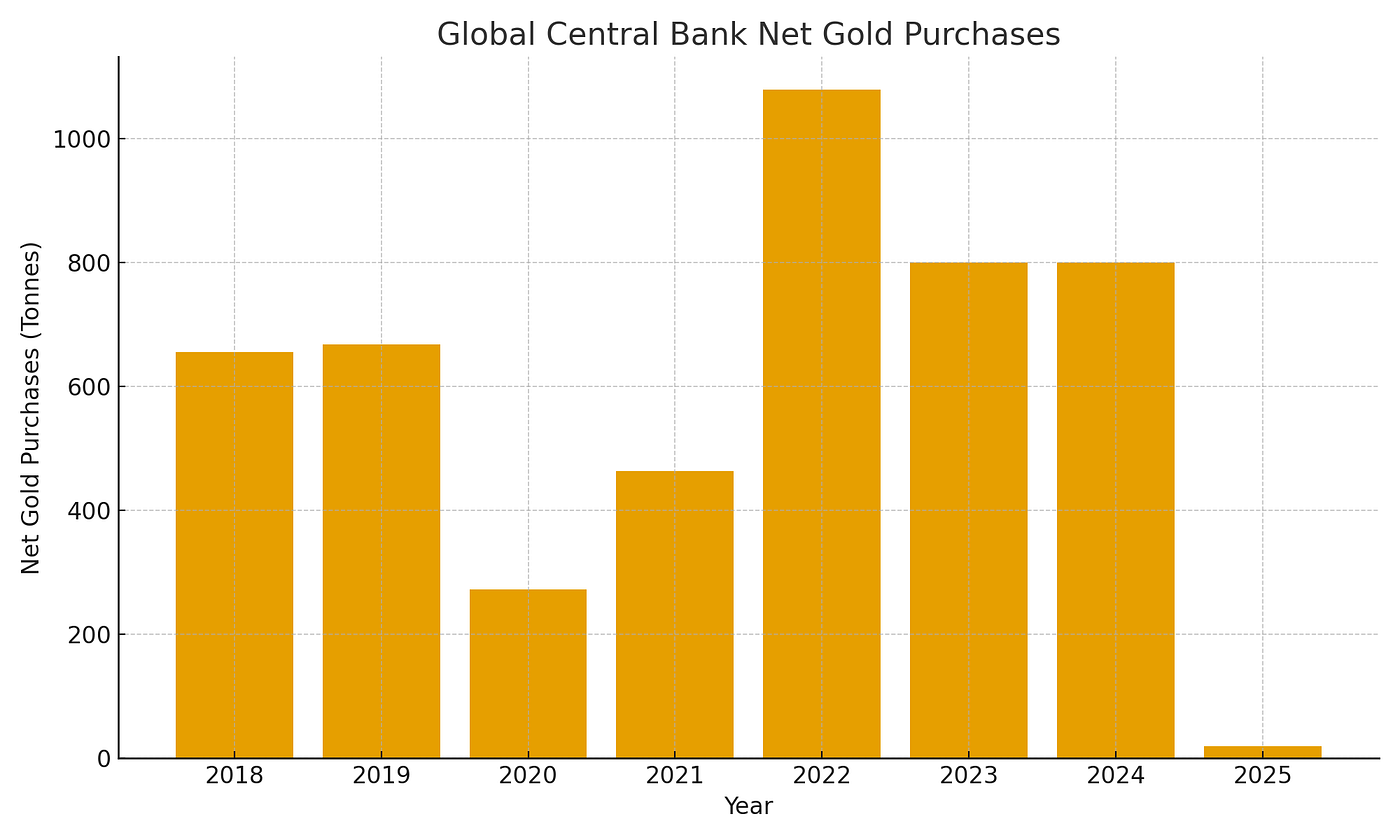

Global central banks purchased:

- 656 tonnes in 2018

- 668 tonnes in 2019

- 273 tonnes in 2020

- 463 tonnes in 2021

- 1,079 tonnes in 2022 (record high)

- ~800 tonnes in 2023

- Ongoing strong accumulation in 2024–2025

This is not random diversification. It is a structural response to a changing global monetary regime.

4.3 Why Gold Is Being Repriced

Drivers of gold repricing:

- Fiscal dominance reduces real yields

- Reserve diversification away from USD

- Financial repression becomes inevitable

- Global geopolitical realignment

- Commodity-based currencies gaining relevance

- Algorithmic rebalancing by sovereign wealth funds

Gold does not need explicit policy changes to reprice; macro structure alone can push gold into the $3,000–$5,000 range over the next cycle.

5. The Case for Explicit Gold Revaluation

5.1 Historical Precedent: The 1933–34 Repricing

During the Great Depression, President Roosevelt:

- Prohibited private gold ownership

- Transferred all gold to the government

- Increased the official gold price from $20.67 to $35 (+69%)

Effects:

- Instant expansion of the U.S. balance sheet

- De facto debt reduction through inflation

- Stabilization of the banking system

- A weaker dollar that supported growth

It was a sovereign-level reset of the monetary base.

5.2 Would the U.S. Revalue Gold Again?

Not through confiscation — modern markets and politic norms make that unnecessary.

However, implicit revaluation through:

- Central bank accumulation

- Shifts in reserve composition

- Global demand dynamics

- Decline in real yields

is already underway.

A move from $2,000 to $4,000 gold would:

- Increase the value of U.S. gold reserves from ~$500 billion to ~$1 trillion

- Strengthen the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet

- Provide implicit inflation without explicit monetization

- Support a controlled devaluation of real debt burdens

This is the “cleanest” form of balance-sheet reset available to sovereigns.

6. Implications for U.S. Treasuries

6.1 Long-Term Yields: Upward Pressure Is Structural

Structural steepening pressures include:

- Record supply

- Declining foreign demand

- Rising term premium

- Persistent inflation risk

- Fiscal dominance limiting real yield increases

These conditions favor:

- Bear steepener trader

- Long-end volatility

- Short-duration preference

- Systematic hedging demand from banks and pension funds

6.2 The Treasury Market as a Global Systemic Risk

Treasuries are the world’s collateral foundation:

- Repo markets

- Derivative margining

- FX swap collateral

- Bank liquidity metrics

- Central bank reserve portfolios

A disorderly selloff would destabilize:

- Mortgage-backed securities

- Corporate credit

- Global dollar funding markets

- Commodity trade finance

- Sovereign debt markets in EM

The Federal Reserve’s role as backstop is now structurally required.

7. Implications for the U.S. Dollar

7.1 A Strong Dollar Short-Term, but Weakening Long-Term

The dollar benefits from:

- Global uncertainty

- Energy transitions

- Capital flows into U.S. tech

- Interest-rate differentials

However, long-term:

- Fiscal dominance

- Reserve diversification

- Structural inflation

- Twin deficits

- Strategic competition with China

all point toward a gradual weakening of the dollar over the next decade.

The path is nonlinear but directional.

8. Strategic Implications for Investors

8.1 Gold: Multi-Year Structural Long

Gold benefits from:

- Fiscal dominance

- Inflation above interest rates

- Central bank demand

- Geopolitical fragmentation

- Reserve diversification

Fair-value estimates under fiscal dominance:

- Base case: $3,000–$3,500

- Fiscal stress case: $4,000–$5,000

- Structural repricing scenario: $6,000–$8,000+

8.2 U.S. Treasuries: Curve Steepening

Positioning themes:

- 2s10s steepener

- Long volatility in the belly

- Tactical trades around supply events

- Hedging via inflation breakevens

8.3 Equities: Higher Nominal Growth, Lower Real Returns

In fiscal dominance:

- Nominal GDP rises

- Earnings inflate

- Multiples compress

- Volatility regimes shift upward

Quality, pricing power, and real assets outperform.

8.4 Cryptoassets: Beneficiaries of Real-Yield Suppression

Crypto assets, especially Bitcoin, act as:

- Non-sovereign collateral

- High-beta macro trades

- Liquidity-sensitive assets

Fiscal dominance is structurally supportive for this segment.

9. Conclusion: A New Macro Regime Defined by Fiscal Constraints

The United States has entered a structural phase in which fiscal realities dominate monetary policy. The sovereign debt burden, rising interest expenses, and declining foreign demand for Treasuries have created a macro environment where the Federal Reserve must balance inflation control against the risk of destabilizing the government’s financing capacity. Inflation, not legislation, now defines the true limit of U.S. sovereign borrowing.

In this environment:

- Gold becomes a strategic reserve asset, with significant repricing potential

- Treasury yields face structural upward pressure, especially on the long end

- The dollar enters a long-term gradual weakening phase

- Fiscal dominance reshapes global portfolio construction

The global monetary system is shifting from a unipolar, dollar-centered structure toward a more multipolar reserve environment in which sovereign risk, inflation dynamics, and alternative assets play a greater role. Investors who understand these shifts will be positioned advantageously in the decade to come.